The algorithms of Google and the like are relieving people of more and more decisions. While this is largely to their benefit, it is also sometimes non-transparent and with hidden motives. In this interview, author Daniel Kehlmann draws parallels between the printing press and Facebook and talks about the power of stories and novels.

We are living in a time when entertainment and distraction are on offer everywhere. Does this pose fierce competition for authors requiring a high level of concentration from their readers?

This is certainly a problem. I myself also read less than I did 15 years ago. But I also notice that I’m starting to watch fewer TV series again. There was a time when I felt I was constantly watching television. But then the series started to bore me. Television series are nowadays designed to be endless – one season follows on from the next. That’s why I’d rather read a book, because I know I have to read another hundred pages and then this particular book will be finished.

You’re a father. Are there a lot of books in your son’s bedroom?

He also prefers watching films to reading books. And he prefers comics to books without illustrations. However, right now I’m reading him Lord of the Rings. It devotes 20 pages just to describing the landscape, but the story is so powerful that he doesn’t get bored. This serves to restore my confidence in the power of storytelling.

Storytelling takes time. Do you also see your novels as a kind of alternative to the fast life in the age of Twitter and Facebook?

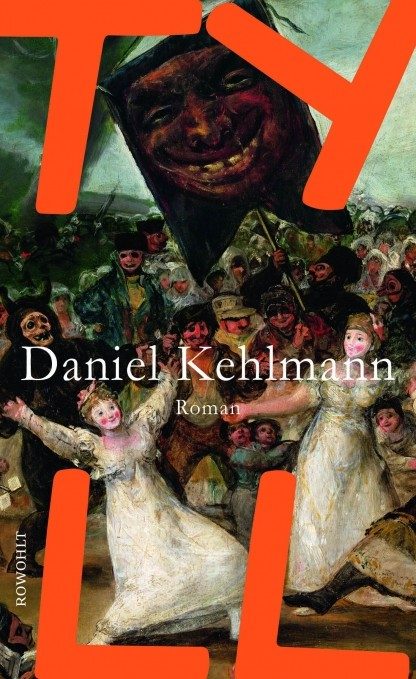

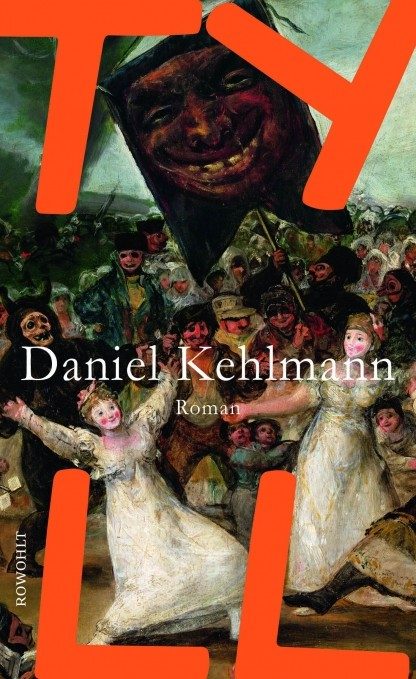

Yes, absolutely. That’s the nice thing about novels. They really go into depth. A novel is in every sense anti-Twitter. That applies not just to me as an author (I spent five years working on my novel Tyll), but also to the readers who take time to address something in more depth.

What is your own attitude to digital media? Joy or aversion?

Not aversion, no. But Facebook is jointly responsible for almost all the bad things that have happened recently in the world. Without the disinformation campaigns operating via Facebook, there would be neither Brexit nor Donald Trump nor Bolsonaro in Brazil. We are currently in a state of collective confusion of a sort similar to that in the decades following the invention of the printing press. Back then the world was flooded with pamphlets and all kinds of propaganda. But then people learned how to handle it.

Is it a question of how much collateral damage we allow ourselves in this learning period?

Exactly. But I’m not particularly pessimistic about this and I think we’ll learn. Nevertheless, the damage is already enormous today for countries such as England, for example.

We can’t determine everything ourselves with social media because there are algorithms working in the background that we are unaware of. Does this give you cause for worry?

This self-empowerment by algorithms is an enormous problem. Where there appears to be an availability of information, in reality the information that we receive is filtered by algorithms. And these algorithms monitor us and pursue their own interests – they want us to click on specific things. This is a problem that needs to be solved politically.

Is it our comfort that is responsible for making us sacrifice freedoms to receive personalised suggestions from computers instead?

We are undoubtedly sacrificing a great deal of self-determination. But we are being offered some things in return, as we wouldn’t do it otherwise. For example, I always use Google Maps. I’m someone who previously always used to get lost. I find it great that I’m now able to find my way around in strange cities. At the same time I’m also obviously disclosing large quantities of personal data and Google is using this to earn money. In today's world we face these decisions on a daily basis and almost always solve the problem in favour of our personal comfort. And I’m no exception.

You’ve delved deep into history for some of your novels. Was everything really better in the past?

On the contrary, almost everything was worse. It really was. We’re extremely fortunate to be alive today. While we have been sitting here, the news has come in that the second patient has just been cured of Aids. There’s a good chance that cancer could be overcome in 20 to 30 years. The advances made by medicine just recently are incredible. The world may have been more poetic in the past, but people suffered pain literally all the time. So we have something to be grateful for.

Medical advances are also enabling us to live increasingly longer. Do you look forward to being 100 years old?

I hope I’ll live to be old but I’m not looking forward to being old (laughs).

Daniel Kehlmann

Writer

Daniel Kehlmann, born in 1975, is one of the most successful writers of post-war German literature. Kehlmann published his first novel Beerholms Vorstellung at the age of 22. He gained international renown at the latest with the publication of Measuring the World that was not only translated into 40 languages, but in 2006 was also one of the best-selling books in the world. In his latest work Tyll, Daniel Kehlmann has the jester Till Eulenspiegel live through the Thirty Years’ War. Kehlmann has received many international awards, including the Candide Award and the Award of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation.